An end-to-end quantum algorithm for CFD simulations, and its application to non-trivial incompressible flows

Key insights

Researchers from PsiQuantum and Airbus have developed the first end-to-end fault-tolerant quantum algorithm for non-linear computational fluid-dynamics (CFD) simulations of incompressible fluids based on the Carleman linearization approach and the lattice-Boltzmann method (LBM).

Even with modern CPU and GPU clusters, many industrially relevant turbulent scenarios remain out of reach, which motivates looking at quantum representations of CFD problems that use the exponentially large space of qubits to manipulate the large amount of information.

The researchers start with the discrete Boltzmann equation with Bhatnagar-Gross-Krook (BGK) collisions, map the solution space onto a lattice, and linearize the nonlinear streaming and collision updates using the Carleman method, thereby creating a large linear system for the quantum computer to process. In absence of a fault-tolerant quantum computer of the required size, the researchers conducted numerical simulations using a matrix-based Carleman-LBM solver and compared the results to the output of a standard LBM solver for computationally tractable cases.

Three significant results have come out of this work:

There is a Reynolds number beyond which adding higher-order Carleman terms leads to divergence of the solution: in 1D it is ~100, and it is expected to be higher in higher dimensions; it was not possible to determine the exact onset for higher-dimensional cases because of computational limitations.

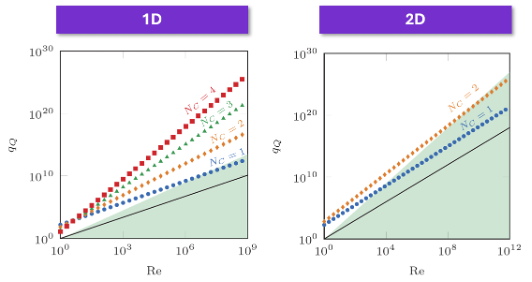

There is a runtime advantage for CFD calculations on a quantum computer with respect to the classical solver. E.g., in 2D the scaling can at most be improved by a factor of Re^0.75, and numerical observations put it closer to Re^0.538. Extracting observables adds an additional cost, e.g., Re^0.375 for the drag force.

Adding realistic CFD conditions, e.g., walls, inlets, outlets, and forcing, does not destroy the scaling of the runtime advantage, rather adds constant multiplicative pre-factors, making this approach worthwhile for realistic industry relevant problems.

Context setting: the challenges of non-linear CFD

Understanding the behavior of fluids such as air or water is a key requirement for several areas of engineering sciences, such as civil or aeronautical engineering. In many instances, physical experiments that would serve to confirm or falsify hypotheses are either impossible or prohibitively expensive; there, high-fidelity computational fluid-dynamics simulations (CFD) are indispensable for engineers. Researchers studied the incompressible Navier-Stokes equations which capture the behavior of the most problems that are simulated by CFD.

As solving the Navier-Stokes equations analytically is a difficult challenge, multiple methods have been developed to facilitate solving them numerically, including finite-volume, spectral-element, or lattice-Boltzmann methods. Large-scale versions of those simulation methods are run on large CPU and GPU clusters in supercomputers to capture the necessary details at the required resolution. Such large clusters are required because these simulations are costly, as the problem complexity grows quickly with the relevant problem parameters (e.g., number of time steps, number of spatial points, the Reynolds number, the Mach number, and more). However, even these large-scale computational resources are frequently not sufficient for all the simulations that researchers want to perform.

In this work on incompressible flows, we focus on the lattice-Boltzmann method (LBM) where we start from the discrete-Boltzmann equation (DBE), where the local collision term is chosen to be the Bhatnagar-Gross-Krook (BGK) collision operator. The equilibrium particle density in the BGK operator contains the non-linear term proportional to velocity squared, making the DBE non-linear. The solution of the DBE is given on a regular lattice grid, which gives the lattice-Boltzmann equation (LBE) its name.

Speaking from the point of classical computation, solving CFD simulations for turbulent flow requires a lot of memory, which is where encoding all the required information in probability amplitudes of qubit registers could be of help, given that superposition and entanglement allow for an exponentially large storage space. However, the non-linearity must be eliminated before solving the problem on a quantum computer. This is because a quantum computer can only implement linear evolution given that it, like any non-relativistic quantum system, is fundamentally governed by the Schrödinger equation, which is a linear equation. In the quantum computing community, the Carleman embedding approach was recently investigated as a potentially suitable method of linearization. The Carleman approach introduces new variables that are higher-power monomials of the non-linear variable up to a desired degree, thereby creating a system of linear equations and simultaneously exploding the memory requirements as the linear number of non-linear variables is replaced by an exponential number of linear variables. Again, the exponentially large storage space of qubits should help with this.

That assumption has featured in past works examining the use of Carleman embedding as an initial step before applying a quantum linear solver algorithm (QLSA). Unfortunately, those earlier works did not fully address whether the Carleman embedding actually converges for realistic Reynolds numbers, how the condition number of the embedded system scales, or how difficult it is to extract observables from the resulting quantum state after the QLSA is applied.

Novel research

Researchers from PsiQuantum and Airbus have examined closely the question of convergence of the Carleman method, and they have devised an end-to-end quantum algorithm employing Carleman embedding, solving the LBE, and examining what the impact of extracting drag as an observable is. After that, they examine three realistic conditions for CFD simulations: the driven Taylor-Green vortex, a lid-driven cavity, and the flow past a cylinder.

The end-to-end algorithm starts from the incompressible LBM with BGK collisions and encodes the streaming and collision updates as a discrete Carleman embedding: all monomials up to order NC are collected into a Carleman state vector Y, and a single time step becomes a sparse linear map Yk+1 = AYk. This is then further expanded by stacking all the time step vectors Yk into a history state YH and constructing a very large sparse linear map AHYH = b, where b is a vector containing the initial condition yini.

On a quantum computer, this matrix equation would be solved using QLSA. In the absence of a large-scale quantum computer, the researchers constructed a classical Carleman-LBM solver and compared it to a standard LBM solver to examine the potential for quantum advantage and the convergence of the Carleman embedding.

Once devised, the solver was applied to three realistic conditions for CFD: the driven Taylor-Green vortex, a lid-driven cavity, and the flow past a cylinder. At the algorithm level, this required that the Carleman-LBM framework be expanded to include walls, inlets, outlets, and forcing. This was done by modifying the streaming matrix S to account for the effect of walls, inlets, and outlets, and including a driving matrix D that includes the effects of forcing.

The first important result is that Carleman embedding does not always converge with increasing order terms included; rather, there appears to be a crossover point after a certain Reynolds number. In 1D, that crossover point is at a Reynolds number of ~100, while it is expected to be higher in higher dimensions. The crossover point is expected to exist for physically relevant settings, but limitations in classical computation prevented pinpointing the exact crossover point in the regimes considered in this work.

The second important result is that there is a region of quantum advantage for CFD calculations that can be expected with increasing Reynolds number. However, that quantum advantage is not exponential; rather, it is polynomial with respect to classical techniques, e.g., in 2D the best improvement of the scaling by a factor of Re^0.75, and numerical observations estimate the factor to be Re^0.538. Extracting observables then adds an additional cost that modifies the improvement factor, e.g., extracting the drag force adds a factor of Re^0.375.

Figure 1: Query complexity. There is a region of potential quantum advantage for higher Reynolds numbers and lower-order Carleman linearization (green area above the black diagonal line). This speed-up accounts for the data extraction step as well.

The third important result is that introducing realistic geometry and fluid-flow conditions does not introduce another Reynolds-number scaling; rather, it introduces a constant multiplicative factor, which indicates that quantum advantage can still be achieved in those conditions. Numerical simulations show that the Carleman embedding converges in the three realistic cases that were examined. It is expected that one could realize a quantum advantage in recovering the drag force from those simulations with increasing Reynolds number.

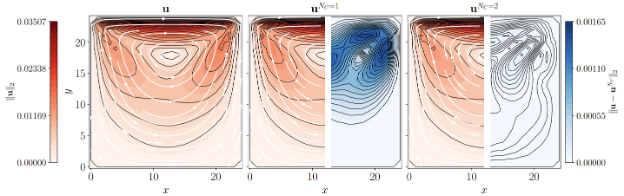

Figure 2: Comparison of the standard LBM solver and the Carleman-LBM solver for a lid-driven cavity. Spatial form of the classical LBM and Carleman LBM solutions (red) and their associated error (blue) for the lid-driven cavity flow after 10 advection times for β=1 and Re=25. Left: the standard LBM-solver solution. Middle: linear Carleman approximation. Right: the quadratic Carleman approximation.

Conclusion: bounded but identifiable quantum advantage for realistic CFD conditions

Taken together, the two papers provide a solid technical picture of what a quantum lattice Boltzmann algorithm can realistically deliver for incompressible CFD. The researchers begin by constructing a fault-tolerant pipeline that starts from an incompressible DBE, embeds its nonlinear collision update into a finite-order Carleman system, solves the resulting global linear system with a QLSA, and examines how to extract the drag force from the solution in the quantum computer. The main result is that any end-to-end speedup over the best-in-class classical methods is at most polynomial in Reynolds number, with no generic exponential advantage available for this problem class.

This end-to-end framework is then extended to realistic conditions with walls, inlets, outlets, and forcing. This is done by modifying the matrices in the Carleman embedding in a way that introduces a controlled overhead without changing the asymptotic scaling in the Reynolds number or closing the window for quantum advantage. A fully matrix-based classical Carleman-LBM solver, benchmarked on the driven Taylor–Green vortex, lid-driven cavity, and the flow past a cylinder, shows that within the Reynolds-number range studied, the Carleman truncation converges.

The important outcome of this research is that there is a clearly defined, rather than speculative, parameter window where a future fault-tolerant quantum device offers a bounded polynomial runtime gain.

What’s next?

Looking ahead, more work should be devoted to stress-testing and refining the end-to-end quantum lattice-Boltzmann pipeline in both the algorithmic and application sides. On the algorithmic side, this means better preconditioning strategies, problem-specific block encodings for geometry and forcing, and potentially alternative linear embedding schemes tailored to particular CFD problems. All these efforts are aimed at improving the condition numbers and overall complexity of quantum solvers without changing the basic lattice-Boltzmann formulation. On the application side, this means pushing the analysis to 3D, exploring higher Reynolds-number flows, and investigating more industrially relevant geometries and boundary conditions. All this should be done while tracking how the Carleman truncation order and convergence radius behave in those regimes. One additional consideration is the investigation of other observables, as the current work only covers drag forces.

Right now, modest but nontrivial quantum advantage seems possible for carefully chosen incompressible lattice-Boltzmann problems, but the next step is to see whether this advantage survives once researchers scale to 3D, higher Reynolds numbers, more complex boundaries, and more demanding observables. The current hypothesis is that it does; however, this must be verified.

Terminology

-

A dimensionless number comparing inertial to viscous forces in a fluid; a higher Reynolds number typically means more turbulent flow.

-

A CFD simulation method that evolves particle-density distributions on a lattice instead of directly working with velocity and pressure in the Navier-Stokes equations. Streaming and collision steps together recover the macroscopic Navier–Stokes equations.

-

A linearization that turns a nonlinear system into a linear one by tracking all products of variables up to a chosen order. Truncating at finite order approximates the original nonlinear dynamics with a high-dimensional linear system.

-

A quantum algorithm that prepares a quantum state proportional to the solution of a large linear system Ay = b. It assumes that A and b can be efficiently encoded on a quantum computer.

Simulating quantum chemistry and partial differential equations (PDEs) is critical for modeling an important range of chemical and physical systems, including for common and complex applications in aerospace. On January 13, 2026, PsiQuantum announced that the company is collaborating with Airbus, Europe’s largest aeronautics and space company, to advance applications in aerospace for fault-tolerant quantum computers. Learn more from the company’s announcement.